First and foremost we must understand that Shakespeare's texts were created through a collaborative process specific to the early modern period. This collaboration took many possible forms with regard to the initial writing of the play, including: working with other playwrights to create a play (for example, The Two Noble Kinsmen and Henry VIII with John Fletcher), to "fixing" or "adapting" other playwrights work for a specific acting company, or even plagiarizing bits of text from other playwrights, poets, and historians (Several pieces of Shakespeare's history plays are taken almost verbatim from Holinshed's Chronicles).

Yet, a second type of collaboration needs attending to when one considers Shakespeare's process for creating a text: the play in performance. Shakespeare was a man of the theatre. He acted in his own plays and in the plays of other writers performed by his company. He was involved in the rehearsal process and changes were made to the text to suit performance conditions. An extra line might be added to provide more time for a quick change, an actor (particularly the comic actor William Kempe) might ask for a change of script to include a dance or other interaction with the audience. Any number of additions and subtractions occurred in the process of realizing a text for performance. Indeed, even the seemingly standard five-act structure of most of Shakespeare's plays was added with the First Folio. As James Hirsh points out, "of the 74 plays for the adult companies printed between 1591 and 1607, five plays by Ben Jonson are the only ones divided into acts" (Hirsh 220). Even further, additional changes could be rendered in the printing process.

Yet, a second type of collaboration needs attending to when one considers Shakespeare's process for creating a text: the play in performance. Shakespeare was a man of the theatre. He acted in his own plays and in the plays of other writers performed by his company. He was involved in the rehearsal process and changes were made to the text to suit performance conditions. An extra line might be added to provide more time for a quick change, an actor (particularly the comic actor William Kempe) might ask for a change of script to include a dance or other interaction with the audience. Any number of additions and subtractions occurred in the process of realizing a text for performance. Indeed, even the seemingly standard five-act structure of most of Shakespeare's plays was added with the First Folio. As James Hirsh points out, "of the 74 plays for the adult companies printed between 1591 and 1607, five plays by Ben Jonson are the only ones divided into acts" (Hirsh 220). Even further, additional changes could be rendered in the printing process.

Key Terms

Foul Papers: The author's own copy of the play, written on loose sheets (front and back) in Secretary hand. As the name denotes, these are notriously difficult to read, and only a few pages from Sir Thomas Moore are believed to include Shakespeare's own hand (Included as the main image on this page).

Fair Copy: A copy of the foul papers created by either the author or a professional scribe to make it legible for the theatre.

Book of the Play: the fair copy, as it came to be adjusted by a theatre company for performance. It would include additions, subtractions, and more information on theatrical business, etc. This was the most valuable copy of the play for an acting company during this period.

First Folio: The publication of 37 of Shakespeare's plays, published in 1623 by John Heminges and Henry Condell. These texts are published from copies in three areas: previously published quartos, Shakespeare's own manuscripts, and transcripts and manuscripts owned by the playhouse (and some from Ralph Crane, a scribe often used by The King's Men).

Quartos: Half of the plays (18) published in the first folio, were first published in Quarto form (many during Shakespeare's own life). In several cases, multiple quarto versions exist for a particular play. In the case of Romeo and Juliet, for example, there are two quartos and the folio version. Sometimes quartos receive a negative critique and are deemed "bad," but recent scholarship has begun to view these works as earlier drafts or most intriguingly as versions that demonstrate more closely how the play was presented in performance. For an excellent introduction to the Romeo and Juliet First Quarto and quartos in general see Lukas Erne's work in the resource list below.

Construction of Folios and Quartos

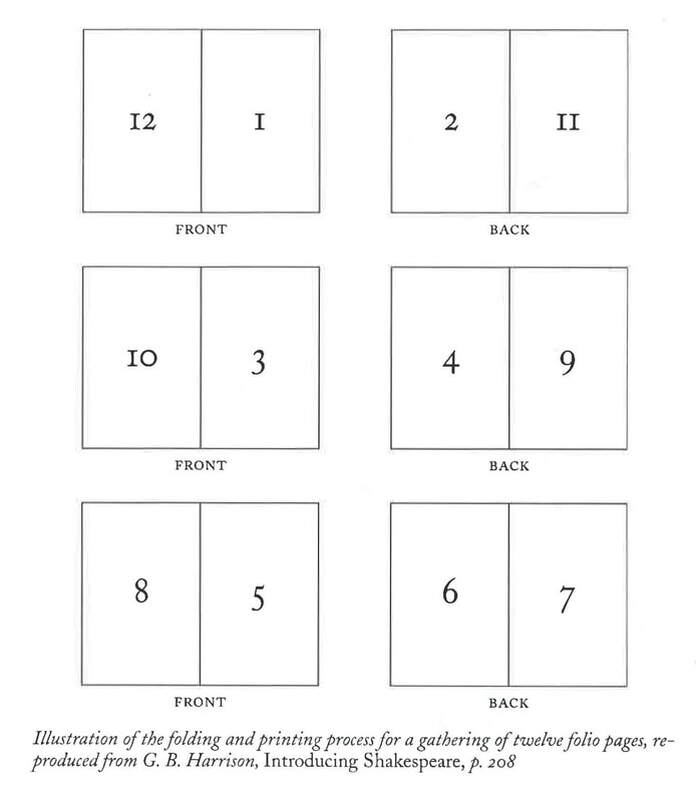

The image shows the 6 sheets used to print 12 pages of the First Folio in 1623. Reproduced from McDonald, 80

The image shows the 6 sheets used to print 12 pages of the First Folio in 1623. Reproduced from McDonald, 80

Printing during the Renaissance period consisted of folding one variously sized "sheet" in multiple ways depending on the size of book to be published. One sheet was roughly 18 x14 inches and was handmade (thus quite expensive). A Folio edition of a book meant that a "sheet" was folded only one time, creating a. finished book of around 9 x 14 inches. Quartos were folded twice creating a book of around 7 x 9 inches. For a Folio this meant that one sheet would have 4 pages of text printed on to it (front and back), while a Quarto would have a total of 8 pages of text printed on it (front and back). Obviously, this made the printing process fairly complicated (even more so in quartos as a total of 8 pages were printed on one sheet (front and back). Below is an image reproduced from G. B. Harrison's Introducing Shakespeare (pg 208) demonstrating a fathering of six sheets for folio printing and what that meant for each page printed in the sequence. As you can see, Page 1 and Page 12 were printed on the same side of one sheet and following the pattern then of 11 and 2 on the back side of the same sheet. Sheets would be printed separately then collated into gatherings of 6 sheets (12 pages) to be tied together into a completed Folio. When working on a gathering, printers started in the middle of the texts in the 12 page portion, typesetting and printing pages 6 and 7 first, and building out. A similar process was used for Quartos. While working in this way, Printers necessarily had to make some guesses about how much text would fit to a page, so as to avoid any wasted paper (this was called "casting off copy"). This process of guessing sometimes caused problems as outlined by Russ McDonald with regard to the last page of the Quarto text of King Lear: "the printer apparently had to squeeze text on the last page available to him. Consequently we see evidence of corner-cutting: two short speeches are run together on the same line; The Duke of Albany's sympathetic tribute to Lear is converted from verse to prose, which takes less space. The need for economy may also explain why a word is dropped ("great" in "this great decay") and the stage direction for Lear's death is omitted" (201).

Thus, the printing process represented another mode of collaboration in which Shakespeare's work was perhaps altered, edited, or just mistaken in the hurly burly of the printing shop, which was admittedly loud and filthy. For example, the leather print balls used to place ink on the press had to be kept soft and were thus soaked in human urine, likely attracting a large number of flies (McDonald 201). My favorite example of the textual instability caused by printers is the case of the last four lines of Titus Andronicus as printed in the Folio of 1623:

"See Iustice done on Aaron that damn'd Moore,

From whom, our heauy happes had their beginning:

Then afterwards, to Order well the State,

That like Euents, may ne're it Ruinate"

As McDonald points out, Scholars, using a technique of analytical bibliography, have determined that the Folio was copied from the third quarto of Titus (1611) which was copied from the second quarto. The first quarto of Titus, however, does not contain the above final lines (There is only one copy of this quarto in existence, which was discovered in the early 1900s in Sweden). Based on textual analysis it appears clear to these scholars that the last three leaves of the first quarto used to set the second quarto were damaged and the compositor in the print shop reconstructed the end as best they could, clearly going too far in the ending of the play.

Thus, the printing process represented another mode of collaboration in which Shakespeare's work was perhaps altered, edited, or just mistaken in the hurly burly of the printing shop, which was admittedly loud and filthy. For example, the leather print balls used to place ink on the press had to be kept soft and were thus soaked in human urine, likely attracting a large number of flies (McDonald 201). My favorite example of the textual instability caused by printers is the case of the last four lines of Titus Andronicus as printed in the Folio of 1623:

"See Iustice done on Aaron that damn'd Moore,

From whom, our heauy happes had their beginning:

Then afterwards, to Order well the State,

That like Euents, may ne're it Ruinate"

As McDonald points out, Scholars, using a technique of analytical bibliography, have determined that the Folio was copied from the third quarto of Titus (1611) which was copied from the second quarto. The first quarto of Titus, however, does not contain the above final lines (There is only one copy of this quarto in existence, which was discovered in the early 1900s in Sweden). Based on textual analysis it appears clear to these scholars that the last three leaves of the first quarto used to set the second quarto were damaged and the compositor in the print shop reconstructed the end as best they could, clearly going too far in the ending of the play.

Sources and Further Reading

McDonald, Russ. "Chapter 6: What Is Your Text?" The Bedford Companion to Shakespeare: An Introduction with Documents, 2nd edition (Bedford, St. Martin's, 2001) 194-210.

Erne, Lukas. "Introduction." The First Quarto of Romeo and Juliet 1St paperback ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011.

Erne, Lukas. "Introduction." The First Quarto of Romeo and Juliet 1St paperback ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011.