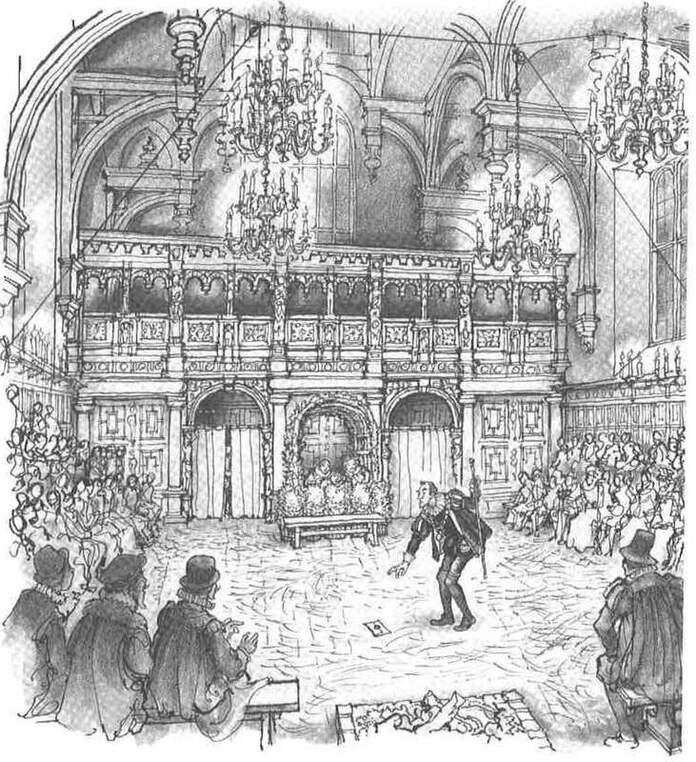

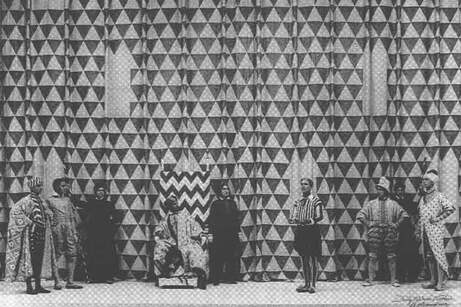

Fig 1. a speculative rendering by C. Walter Hodges of Twelfth Night's presentation at Middle Temple Hall in 1602 on Candlemas (Feb 2).

Fig 1. a speculative rendering by C. Walter Hodges of Twelfth Night's presentation at Middle Temple Hall in 1602 on Candlemas (Feb 2).

The first documented production of Twelfth Night occurred on February 2, 1602 at Middle Temple Hall (one of four Inns of Court which are essentially a school for barristers or what we might term lawyers today) as recorded by John Manningham in his diary:

“At our feast [Candlemas feast] wee had a play called ‘Twelfth Night, or What You Will’, much like the Commedy of Errores, or Menechimi in Plautus, but most like and neere to that in Italian called Inganni. A good practise in it is to make the Steward believe his Lady Widdow was in love with him, by conuterfeyting a letter as from his lady in general termes, telling him what she liked best in him, and prescribing his gesture in smiling, his aparaile, &c, and then when he came to practice making him believe they tooke him to be mad” (qtd. In Donno 1).

While this is the first solid piece of evidence that we have for production there is a great deal of speculation dating the initial performance to January 6 in 1601 by Leslie Hotson, where he argues that the performance was part of a celebration attended by both the Queen and an Italian visitor by the name of Virginio Orsini (Duke of Bracciano). Sadly, despite some surviving evidence about the night's festivities (for example, we do know that The Lord Chamberlain’s Men performed), the title of the play is unknown. Based on contemporary references found within the text, we can say that it was written and likely performed sometime between 1600 and 1602. The only other known performances in the early 1600s occurred in 1618 and 1623 at court.

“At our feast [Candlemas feast] wee had a play called ‘Twelfth Night, or What You Will’, much like the Commedy of Errores, or Menechimi in Plautus, but most like and neere to that in Italian called Inganni. A good practise in it is to make the Steward believe his Lady Widdow was in love with him, by conuterfeyting a letter as from his lady in general termes, telling him what she liked best in him, and prescribing his gesture in smiling, his aparaile, &c, and then when he came to practice making him believe they tooke him to be mad” (qtd. In Donno 1).

While this is the first solid piece of evidence that we have for production there is a great deal of speculation dating the initial performance to January 6 in 1601 by Leslie Hotson, where he argues that the performance was part of a celebration attended by both the Queen and an Italian visitor by the name of Virginio Orsini (Duke of Bracciano). Sadly, despite some surviving evidence about the night's festivities (for example, we do know that The Lord Chamberlain’s Men performed), the title of the play is unknown. Based on contemporary references found within the text, we can say that it was written and likely performed sometime between 1600 and 1602. The only other known performances in the early 1600s occurred in 1618 and 1623 at court.

The next reference to productions of Twelfth Night occurs during the restoration period as noted in the diary of Samuel Pepys (a rather important source for restoration theatre as Pepys attended and documented a great deal of theatrical happenings). Pepys saw Twelfth Night three separate times in the 1660s and roundly condemned it each time as a “silly play,” which he thought was weak, and even criticized the play as having nothing to do with January 6th celebrations known as Twelfth Night. Regardless, the play fell from favor in the Restoration and was not “rediscovered” until 1741 at the Drury Lane Theater where it became a star vehicle for actresses in the roles of Viola (Hannah Pritchard) and Olivia (Kitty Clive). Charles Macklin took on the role of Malvolio, which was often considered the starring role for an actor. Sir Toby Belch came to replace Malvolio as the focal point in the productions seen by Pepys as Thomas Betterton (considered the greatest of the restoration actors) took on the role.

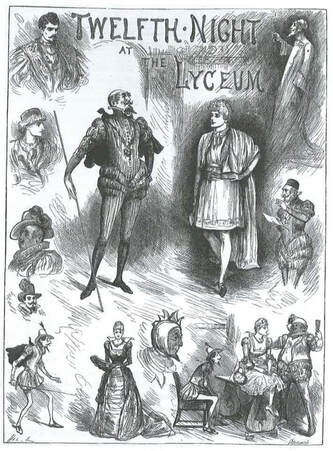

Fig 2. Henry Irving playing Malvolio and Ellen Terry as Viola at the Lyceum Theater, 1884.

Fig 2. Henry Irving playing Malvolio and Ellen Terry as Viola at the Lyceum Theater, 1884.

Revisions of Shakespeare’s text were numerous from the restoration to the 1800s, with scene orders being revised for theatrical and thematic purposes. One such change that has continued into our contemporary moments is the tendency to place the shipwreck scene first and move Orsino’s famous first scene, beginning with the line “ If music be the food of love; play on” (1.1.1), later in the play. By the 1840s; however, popular demand for “original'' Shakespearean performance led theater practitioners back to Shakespeare’s original script and ordering. We must not mistake this desire for “original” as a desire to return to early modern staging practices, but rather an attempt to create through costumes and sets an extravagant historical spectacle of the appearance of early modern England, attempting to recreate Elizabethan streets, palaces, gardens, etc. Throughout the remainder of the 1800s Twelfth Night became a staple of theatrical production focused on spectacle. This can be clearly seen in the advertisement for Henry Irving’s 1884 production of Twelfth Night at the Lyceum Theater in Fig 2.

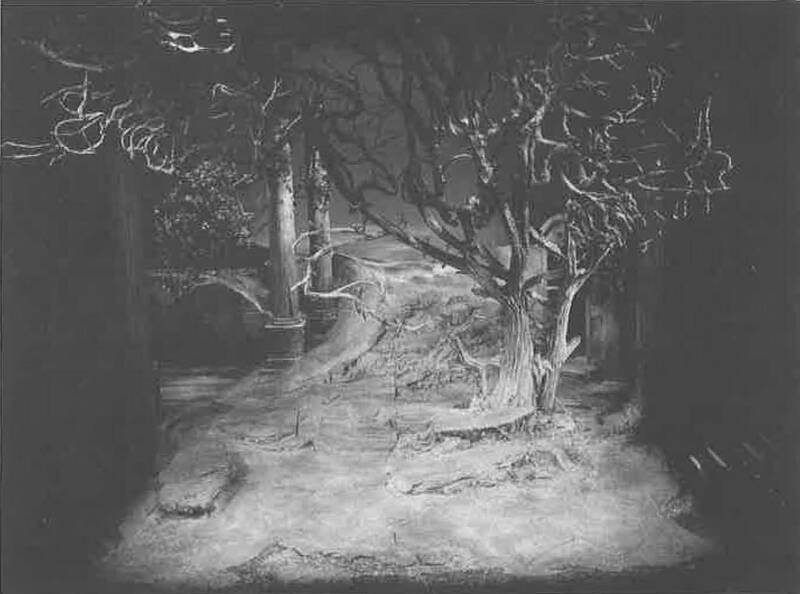

Fig 3. Harvey Granville-Barker's 1912 production. Futurist set design by Norman Wilkinson

Fig 3. Harvey Granville-Barker's 1912 production. Futurist set design by Norman Wilkinson

The early 1900s brought about a modern desire to simplify the spectacle of Twelfth Night performances and returned to the early modern practice of one setting thus allowing for quicker transitions and a faster paced lyricism to the productions as a whole. Most notable was Harley Granville-Barker’s 1912 production which also relied on a simple (if overwhelming) set design by Norman Wilkinson based in futurism and cubism as seen in Fig. 3. The practicalities of the set allowed for the fast paced, virtually uncut performance to impress several contemporary critics while the modernist setting connected the play to themes and ideas of concern to artists in the modernist period: primitivism, individualism vs collectivism, and the nature of art in man’s search for meaning. More traditional performances of the play occurred yearly at the Old Vic Theater in the 1920s and 1930s, and much of the first half of the 1900s was notable for its return to simple settings that allowed for the fast-paced nature of the play.

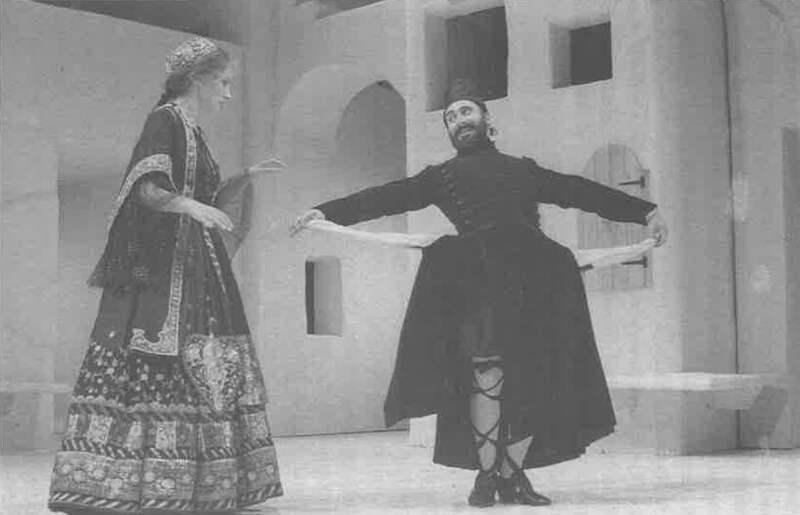

The trend after 1950 consists generally of two modes of performing the play: those focused on the nature of time and the cycle of the seasons and those focused on the place that is Illyria. Those plays focused on time and the seasons often set an autumnal mood combining the serious and comedic elements to a high degree. Begun by Peter Hall’s 1958 production at Stratford, it perhaps was best exemplified in Terry Hands Royal Shakespeare Company production in 1979, where Hands presented “a life-renewing season passage from snow-laden and frosty-branched midwinter to daffodilly spring” (Elam 108). Productions focused on place often used the moment to inaugurate or open a theater, to celebrate the Italian setting of the play in Illyria, to return to Commedia Del’arte forms, or to explore exotic locales and different cultures. For example The Old Vic was reopened in 1950 with a production directed by Hugh Hunt that focused on the Italian setting and included “fake commedia dell-arte clowns” (Elam 110). Conversely, Ariane Mnouchkine’s 1982 Avignon Festival production set the play in India.

Twelfth Night is and was also often adapted with the addition of music to the varying tastes of specific periods. For example, In the late 1700s musical numbers were moved from Feste to Olivia and Viola to show off the star actresses singing prowess. In 1968 Twelfth Night was adapted by Hal Hester and Danny Apolinair as a rock musical titled Your Own Thing in New York City. Countless other examples of musical adaptations and amendments can be found throughout Twelfth Night’s production history, including perhaps the original description of the the potential Twelfth Night performance for Virginio Orsini on January 6, 1601, which was described by the Lord Chamberlain at the time as “that shalbe best furnished with rich apparel, have greate variety and change of Musicke and daunces, and of a Subject that may be most pleasing to her Maiestie” (qtd. In Donno 1). Certainly the description might be said to match a production of Twelfth Night, event if it is uncertain that Twelfth Night was the performance referenced.

A final note on a portion of the production history provided from Keir Elam’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will, Arden Shakespeare 3rd edition. Actors playing the roles of Malvolio, Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, Feste, Orsino, Olivia, and Viola will find interesting sections starting on page 123 that are dedicated to the specific performance history of their respective characters.

A final note on a portion of the production history provided from Keir Elam’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will, Arden Shakespeare 3rd edition. Actors playing the roles of Malvolio, Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, Feste, Orsino, Olivia, and Viola will find interesting sections starting on page 123 that are dedicated to the specific performance history of their respective characters.

Sources and Additional Readings

In Depth Analysis and Description of Performance History:

- Shakespeare, William and Keir Elam. "Make a Good Show On't: Twelfth Night in Performance." Twelfth Night. 3rd Edition, The Arden Shakespeare London: Bloomsbury 2008. 87-145.

- Shakespeare, William and Elizabeth Story Donno. "Stage History." Twelfth Night. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press 2003. 36-52.